“We are too gross to be capable of understanding the signification of the dream, the vision, or the sudden presage, or of divining the source of the premonition, or its purport.”

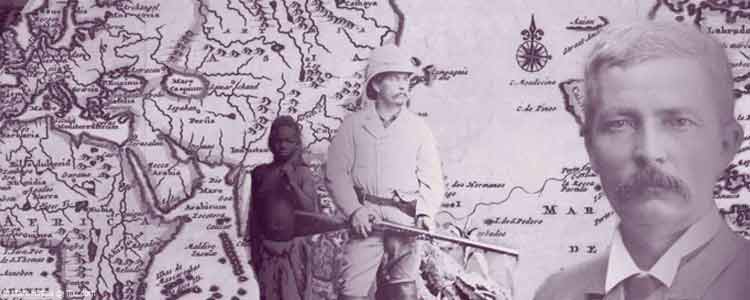

– Sr. Henry Morton Stanly

Crisis Telepathic Dreams

Crisis telepathy may be one of the most common and most widely documented types of telepathic dreams. In these dreams, the sleeping person dreams of a person, normally a loved one, who is in danger or dying.

One such dream is documented by Sir Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904), a British journalist and surveyor known for his exploration of Central Africa during the second half of the 19th century.

Sr. Henry Morton Stanley

Stanley was a native of Wales, UK, and in 1857, he traveled to New Orleans. He worked as a cabin boy aboard the American ship Windermere, and when the American Civil war broke out, he went on to enlist in the Confederate Army. Later, Sir Stanley was injured and taken as a prisoner of war by the Union Army. He managed to secure his release from captivity by declaring his allegiance to the Union.

Aunt Mary

Sir Stanley was the illegitimate son of a farmer and his servant, Elizabeth Parry, who remained unmarried. Stanley never knew his father, as his father died shortly after his birth. He was considered a bastard and given away to the care of his grandfather.

Until age 15, when he began to live on his own, Sir Stanley was raised by his father’s relatives, including his aunt Mary. Stanley’s childhood was filled with neglect and mistreatment. His aunt Mary showed him glimpses of compassion and kindness; he felt closer to her than the others.

The Farewell Dream

While in captivity, Stanley had a dream that he describes as follows:

“On the next day (April 16th), after the morning duties had been performed, the rations divided, the cooks had departed contented, and the quarters swept, I proceeded to my nest and reclined alongside of my friend Wilkes, in a posture that gave me a command of one-half of the building. I made some remarks to him upon the card-playing groups opposite, when, suddenly, I felt a gentle stroke on the back of my neck, and, in an instant, I was unconscious. The next moment I had a vivid view of the village of Tremeirchion, and the grassy slopes of the hills of Hiraddog, and I seemed to be hovering over the rook woods of Brynbella. I glided to the bed-chamber of my Aunt Mary. My aunt was in bed, and seemed sick unto death. I took a position by the side of the bed, and saw myself, with head bent down, listening to her parting words, which sounded regretful, as though conscience smote her for not having been so kind as she might have been, or had wished to be. I heard the boy say, ‘I believe you, aunt. It is neither your fault, nor mine. You were good and kind to me, and I knew you wished to be kinder; but things were so ordered that you had to be what you were. I also dearly wished to love you, but I was afraid to speak of it, lest you would check me, or say something that would offend me.”

“I feel our parting was in this spirit. There is no need of regrets. You have done your duty to me, and you had children of your own, who required all your care. What has happened to me since, was decreed should happen. Farewell.”

“I put forth my hand and felt the clasp of the long, thin hands of the sore-sick woman, I heard a murmur of farewell, and immediately I woke.”

Sir Stanley’s Aunt Mary died the next day, April 17th, 1862 in Fynnon Beuno, Wales, United Kingdom.